Women defend their rights and incomes: lessons from Nepali farmers

Photo (above) - Farmer demanding improved infrastructure in the haat bazaar.

The weekly farmers’ market, locally called haat, beats with life and connects the rural farmers with urban consumers every Tuesday and Friday in Sandhikharka village, Arghakhanchi district in western Nepal. The haat is an open-air traditional market place where rural farmers sell their farm produce to local consumers. Haats are operated once, twice, and occasionally three times a week; they also provide public space for people to meet. This bustling marketplace is not only a lifeline for women farmers, but also a canvas painted with diverse stories.

This story brings you on a journey of the haat's vibrant history and opens up three prominent issues: the closure of a haat during Covid-19 and its implications for women farmers, the intricate reasons for its prolonged shutdown even after Covid-19, and the inspiring tale of collective efforts that resulted in its resumption.

The haat market: through bad times and good

The history of the haat in the village of Sandhikharka dates back five decades to when two farmers, Bishnu Prasad and Shri Krishna, began selling vegetables in the market. That was the time when a largely subsistence-oriented society barely accepted the idea of selling vegetables or fruits. Gradually the market evolved, with the commencement of the commercial production of cauliflower in 1983, which inspired other farmers.

Some farmers like Kaila Majhi imported vegetables from the Southern plains and sold them in dokos (bamboo baskets) in public places. Other vegetable farmers had begun cultivating produce for sale locally, but they still lacked proper places to sell it. This led to the formation of farmers’ groups to foster collective and coordinated efforts to grow and sell vegetables and other agricultural produce.

The Laxmi Vegetables Group was formed in 1988 and its members started selling vegetables in the Khula Manch (open public space) the same year. In 1990, the haat was moved from Manch to Bagaincha (mango fruit orchard) located at the heart of the town. It was then moved again, to a location near Buspark in 2011. Such frequent movement was not in the interest of farmers and consumers but they were compelled to migrate, because of decisions by municipal authority, which officially manages the haat (about which, more below).

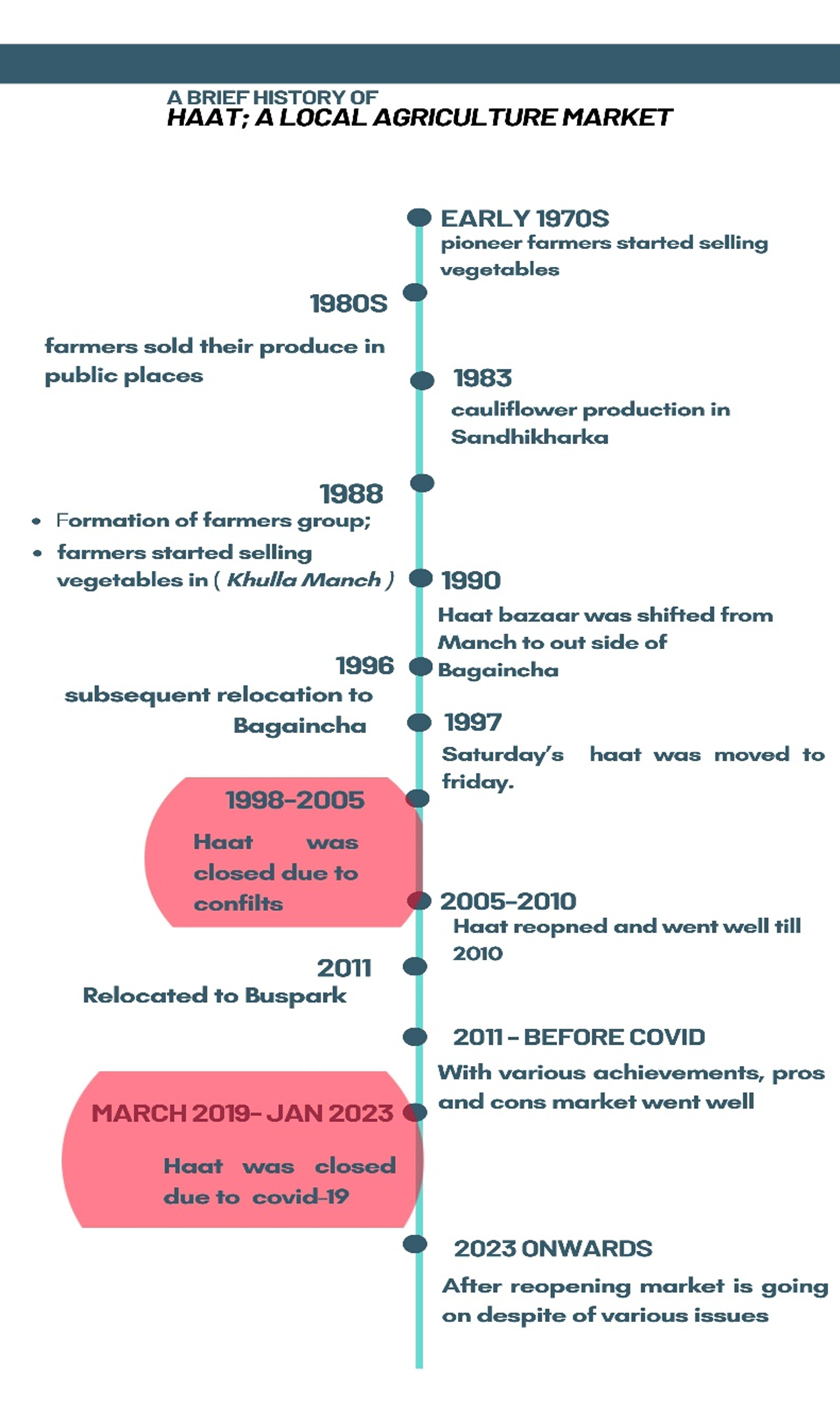

Despite these hurdles, the haat endured until March 2020, when it was closed again due to Covid-19. The figure below summarises the chronology of the haat in Sandhikharka.

The closure had negative consequences on the livelihoods of women farmers and the local agriculture-based economy. Farmers were unable to access the seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, and other inputs they needed for production. At the same time, the livelihoods of women farmers who were dependent on the haat was severely affected. Income from agricultural sales was reduced to almost half of its pre-Covid levels. There was also an issue of payment by intermediaries.

Khimsara (not her real name), a farmer from Kimdanda said:

‘The haat was closed and there was no other option than providing vegetables to intermediaries. They took vegetables almost at half price, on credit, and never made a payment.’

Mobility restrictions and low prices coupled with issues of payment, demotivated farmers from growing vegetables. Bimala, another farmer from Jagata said,

“My fellow farmers and I reduced production of vegetables by more than half during the Covid pandemic and closure of the haat bazar”.

Small women farmers were among the most severely affected by the pandemic.

While small farmers were severely affected by closing of the haat, large farmers were not much affected and large sedentary traders made gains. Intermediaries and traders purchased at a low price from farmers and sold at high prices: low-income consumers had to pay extra. As the market remained locked, large traders also imported vegetables from the lowland plains (Terai) which undercut local farmers wishing to sell their premium vegetables with superior quality, taste, and longer shelf life. Disadvantaged small-scale local women farmers had no alternative but to lower their prices to compete with the imports. Intermediaries and traders reaped substantial profits.

As the district began its journey towards recovery from Covid-19, the haat remained closed. Consequently, small farmers and low-income consumers continued to suffer. Women farmers became suspicious of the forces at play behind the long haat closure. The municipality said the haat should be closed for safety reasons, but farmers indicated that the situation was complex.

Farmers said that the municipality took little initiative, and also failed to stop or punish the people who destroyed temporary stalls in the haat. They suspected that interest groups may be influencing the municipality's decisions.

Women in decision-making and women-targeted measures reignite local trade

Amid this complex interplay of power and business interests, farmers, researchers, municipality, and private sector actors decided to create a deliberative platform, which became instrumental in the eventual opening and effective running of the haat. The Vegetables Production and Marketing Group (VPMG) and research team from Southasian Institute of Advanced Studies (SIAS) held reflective and planning meetings several times on the possibility of re-opening the haat.

The VPMG discussed with the municipality and consulted with stakeholders formally and informally, culminating in a multistakeholder workshop. During this event, women farmers shared their livelihood problems amid declining prices and the shrinking market for their products. The workshop concluded with decisions to re-open the haat and the VPMG executive was subsequently restructured to empower more women farmers as committee members.

The haat reopened in September 2022 – with publicity via notices and local radio. Unfortunately, the reopening was at first a failure. When customers reached the haat, there were no farmers and when farmers came to the haat, there were only a few customers. Farmers and customers alike were not convinced that the market would run again.

The VPMG and the research team jointly reflected on how to deal with the new situation of distrust between farmers and consumers. An informal in-person meeting with women farmers revealed they were afraid they would have few customers at the haat and be unable to sell their vegetables. They also suspected that the intermediaries or traders would play an invisible hand and obstruct the haat’s reopening.

To revive the confidence of women farmers, VPMG members organised meetings, made household visits, and disseminated information through radio and television. In addition, VPMG offered women farmers free transport of their vegetables for an initial four weeks. These concerted efforts contributed to the reopening of haat. Since January 2023, haat has been in its full swing.

With the reopening of the haat, a new chapter has begun. Farmers from Jagata, Kimadada, and nearby villages flock to the market with their fresh produce. As haat experienced a vibrant revival, presence of the women farmers became a testament to the market's rejuvenation.

Among them was Sarita, from Divarna. Sarita made her way to the market with two massive pumpkins and a bunch of fresh green beans. With a hopeful smile, she proudly displayed her vegetables, feeling recognised and valued at the bustling market. Similarly, commercial women farmers from Jagata whose main source of income is generated from haat were feeling proud.

Sarala, another hardworking farmer was lightening her face with a big smile after making a good profit. When being asked about the sale, she replied,

‘I have brought 100 kg of cauliflower and a sack of leafy green vegetables. I sold all of the cauliflower at Rs. 70 per kg within a very short time. If I had to give it to intermediaries or traders, I could hardly get Rs. 40 per kg’.

This reopening not only ushered a market revival but also a new balance in the local power relations. The local municipality and other stakeholders started to recognise, listen, and respond to the voice of small women farmers and VPMG.

Ongoing, urgent issues remain concerning: infrastructure and potential threats from intermediaries and traders, the occupation of prime places in the haat by large farmers, local tax, and sanitation. There also remain sustainability challenges relating to the absence of a permanent structure and a fixed operating place. A deliberative forum in August 2023 discussed these issues and the Mayor expressed commitment to resolve them. He processed for allocating land for the haat and construction of a shed in the near future. (See image (top) of woman farmer demanding better infrastructure.)

Women’s persistence and alliances for women’s rights are effective in local context

This story reveals that the primary victims of a change in the local political and economic context be it conflict or, a crisis like the Covid-19, among others, are the marginalised and voiceless people, in this case women small farmers. The local government that provides guardianship to such people can appear silent, because of the influence of powerful actors.

The case of the successful resumption of the haat shows the significance of constant and collective engagement of women farmers and their representative organisation; in this case, the VPMG. It also demonstrates the importance of deliberation to generate reflections and contributions to meaningful changes.

Finally, the role of researchers remains crucial in organising women farmers and amplifying their voices strongly in the multistakeholder deliberation and influencing local government to respond to their agenda.

All Images - Source: Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies (SIAS)